Since my last post, OneWeb launched 36 new low Earth orbit (LEO) communications satellites (in an effort to rival Starlink, but with a much less ambitious network), then as the COVID-19 lockdown commenced in Europe and many other countries worldwide, abruptly declared bankruptcy. What a bizarre turn of events.

Oneweb, was to be made up of just under 650 satellites at approximately 1,200km altitude, on polar orbits. For a summary of their plans, check out the most recent launch video below:

Now, 650 is a MUCH smaller network than Starlink’s huge LEO network of 21,000 satellites and some of the results showed – greater latency than Starlink and lower throughput – broadband speeds in excess of 400 Mbps and latency of 32 ms, but still a huge improvement on a traditional geostationary communications satellite. Back on 21Mar20, not quite three weeks ago as I write this post, OneWeb launched their third batch of 36 satellites from Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan giving them a total of 74 birds in the sky. I love a rocket launch, so here it is a t-10s for your enjoyment.

So, with a reasonable start to their network deployment, a 2021 launch of their service is looking good… until just six days layer, OneWeb filed for US Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. I’m no accountant and I don’t pretend to understand US bankruptcy law, but this is not like bankruptcy in Australia – where creditors would move in and sell of the assets to try and recoup some of their money, no in the USA, the company keeps operating and reorganises it’s finances to ease the burden on its creditors. In this case however, this statement from OneWeb states that they’re trying to reorganise their finances with a view to continue operations (which at this point in the company’s life, means network deployment). These steps have resulted from failed finance negotiations that were progressing, but fell in a hole when the markets tanked as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

OneWeb have about half of their planned 44 base stations built and another 580 satellites to get into orbit, lets hope that they can get their finances in order to finish out their build because until they do, all they have is a lot of liability.

A quick comparison between OneWeb and Starlink reveals the obvious advantage that Starlink have right now:

This is all very interesting and all, but what’s this got to do with the Telecommunications industry?

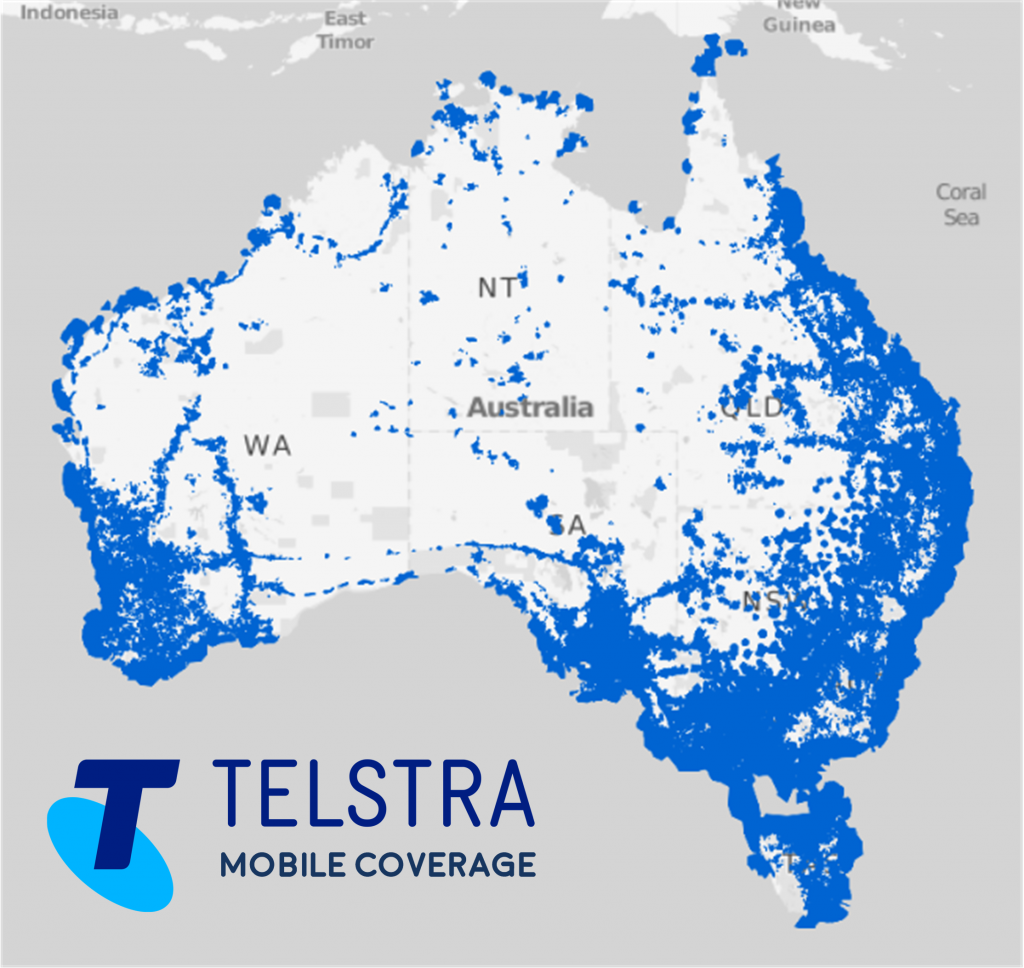

Well, as these players move along with their deployments, it’s going to be harder and harder for Telcos as we know them now to compete against these new companies. If OneWeb can get past these financial problems – and that’s a whole other discussion given the state of the markets as a result of COVID-19 – we could see national CSPs that are focussed on (particularly) IP traffic (lets face it, aren’t they all!) fall to these new competitors.

It all depends on companies like OneWeb and Starlink ability survive this current financial crisis, their price plans and if they can live up to their promised performance. I can’t predict the future, so you and I will need to wait and see…