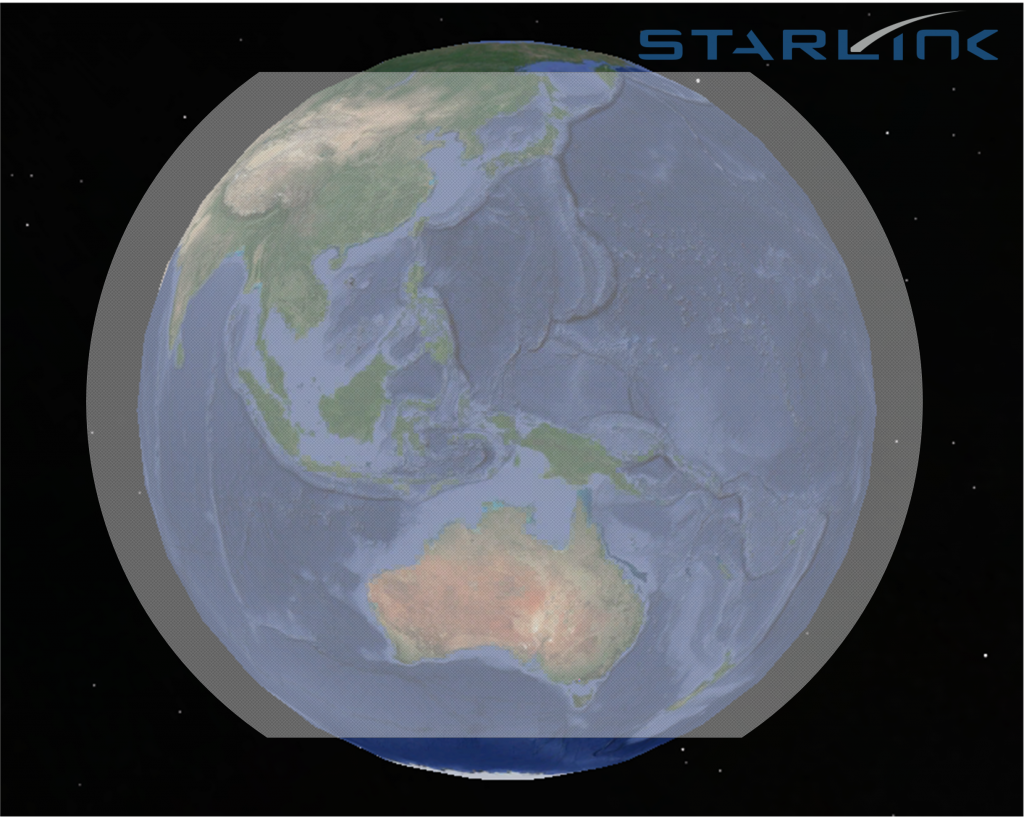

As SpaceX reach 180 starlink satellites in low Earth orbit; on the road to 12,000 once the network is complete, it’s becoming increasingly apparent that Starlink is set to become a global disruptor in the telecommunications industry. Once complete, SpaceX’s network will be nearly global (except for polar regions) and will be ubiquitous. The diagram below illustrates the coverage area – basically 100% coverage of most of the populated regions of the Earth :

The big benefit that the Starlink satellite constellation over a traditional communications satellite sitting in a geostationary orbit is the time it takes for the signal to get from a point on Earth to another Point on Earth. The Starlink constellation at an altitude of 550km is much closer to us than a geostationary communications satellite at (approx) 35,700km. The Starlink constellation will transmit information between Starlink satellites before downlinking to the destination. In an example of a connection between Australia and the Middle East, the diagram below shows the Starlink connection in White, a Fibre (mainly undersea) connection in Red and the geostationary communications satellite connection in yellow. This is approximately to scale.

The white Starlink connection can pretty closely approximate a great circle path and thus is a shorter path than the red fibre connection (which must travel where the undersea cables have been laid). Yes, there are potentially more hops in a Starlink connection than a traditional satellite connection, but the distances involved are MUCH shorter. The other issue with traditional geostationary satellite connections is because of the distances involved, the signal strength is relatively very weak and because of that, these signals suffer from higher data loss, which means that these comms don’t just use standard TCP/IP, rather they use protocols that have much greater error correction and parity capabilities – this has the cumulative effect of slowing down the connection. Combine this slow connection speed and high latency (because of the distances involved), traditional satellite carriers have a big challenge ahead of them when compared to Starlink which promises to deliver much greater speeds at much lower latency – competitive with fibre for all but the largest bandwidth consumers.

To give you an idea of the comparison between Starlink and Geostationary satellite communications, I built a quick animation – remember this is only half of the connection (one way only) ; a real connection would be double the times as the response needs to back to the initiator.

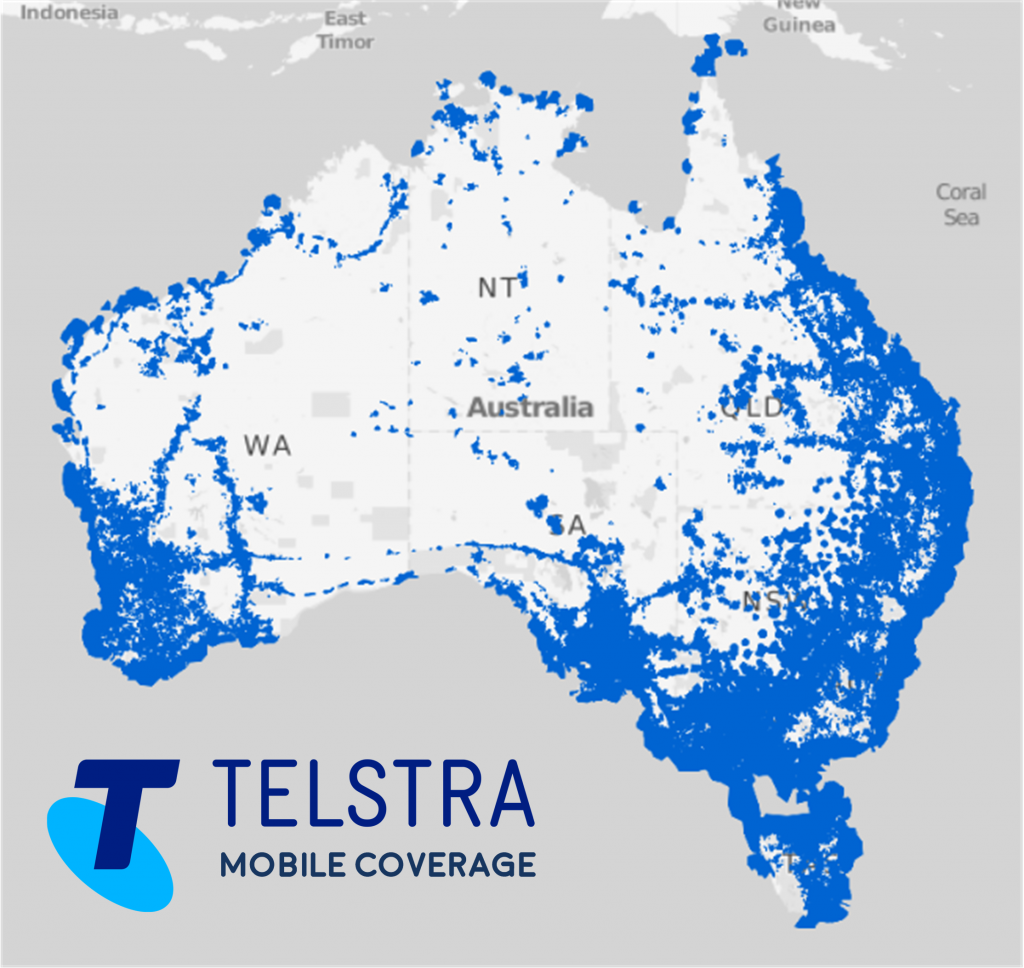

What about for connections between two systems in the same country, as opposed to international connections? Even local in-country CSPs face significant competition from Starlink.

If we look at the Telstra coverage map for Australia+, easily the largest Telco in Australia with the best coverage, and yet we have lots of space that has no coverage at all. Contrast that with a 100% coverage that Starlink would provide with lower latency and much higher throughput… what do you think ? Will Telstra or any other CSP in the world face a challenge from Starlink? I think so…

+ Yes, I know Australia has a very large area and has a relatively small population, so the problem is not as big in other countries, but just imagine 100% coverage 100% of the time and in any country you ever visit…