Originally posted on 13Aug10 to IBM Developerworks (19,781 Views)

Over the past few weeks, I have been watching what seems to be a snowballing issue of governments spying on their citizens in the name of protection from terrorism. First cab off the rank was India a couple of years ago asking Research In Motion (RIM) for access to the data stream for Indian Blackberry users, then asking for the encryption keys. That went quiet until recently (1Jul10), the Indian Government again asked RIM for access to the Blackberry traffic and gave RIM 15 days to comply (See this post in Indian govt gives RIM, Skype 15 days notice, warns Google – Telecompaper). That has passed and the Indian government yesterday gave RIM a new deadline of 31Aug10 (See Indian govt gives 31 August deadline for BlackBerry solution – Telecompaper). In parallel, a number of other nations have asked their CSPs or RIM for access to the data sent via Blackberry devices.

First, was the United Arab Emirates (UAE) who will put a ban on Blackberry devices in place which will force the local Communications Service Providers (CSPs) to halt the service from 11Oct10. RIM are meeting with the UAE government, but who knows where that will lead with the Canadian government stepping in to defend it’s Golden Hair Child – RIM. Following the UAE ban, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon and more recently Indonesia have all said they will also consider a ban on RIM devices. As an interesting aside, I read an article a week ago (See UAE cellular carrier rolls out spyware as a 3G “update”) that suggested that the UAE government sent all Etisalat Blackberry subscribers an email advising them to update their devices with a ‘special update’ – it turns out that the update was just a Trojan which in fact delivered a spyware application to the Blackberry devices to allow the government to monitor all the traffic! (wow!)

Much of the hubbub seems to be around the use of Blackberry Messenger, an Instant Messaging function similar to Lotus Sametime Mobile, but hosted by RIM themselves which allows all Blackberry users (even on different networks and telcos) to chat to each other via their devices.

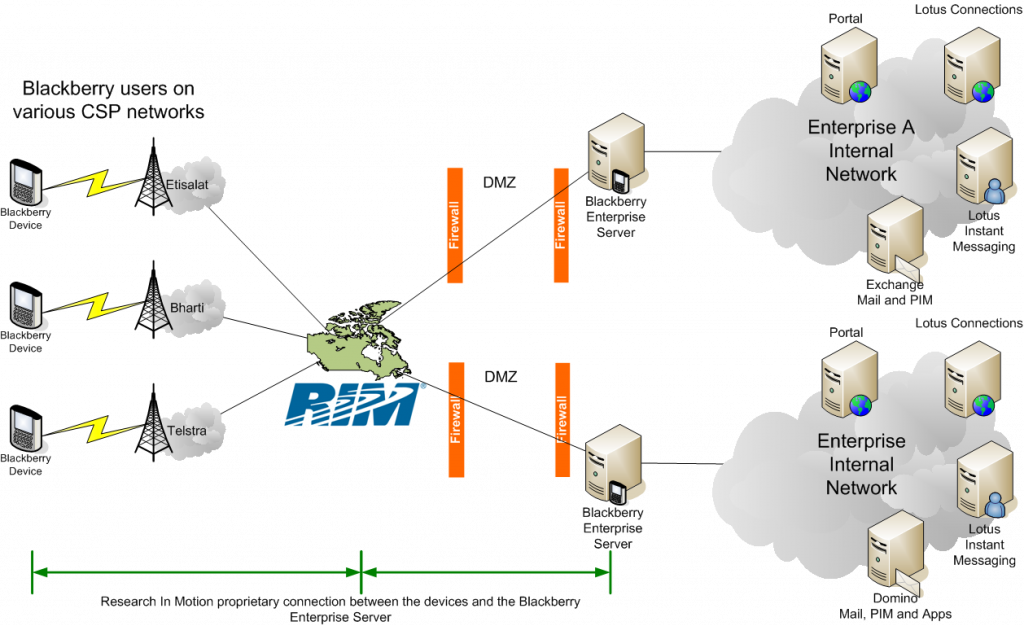

I guess at this stage, it might be helpful to describe how RIM’s service works. From a historical point of view, RIM were a pager company. Pagers need a Network Operations Centre (NOC) to act as a single point from which to send all the messages out to the pagers. That’s where all the RIM contact centre staff sat and answered phones, typed messages into their internal systems and sent the messages out to the subscribers. RIM had the brilliant idea to make their pagers two way so that the person being paged could respond initially with just an acknowledgement that they had read the message, and then later with full text messages. That’s the point at which the pagers gained QWERTY keyboards. From there, RIM made the leap in functionality to support emails as well as pager messages, after all, they had a full keyboard now, a well established NOC based delivery system and a return path via the NOC for messages sent from the device. The only thing that remained was a link into an enterprise email system. That’s where the Blackberry Enterprise Server (BES) comes in. The BES sites inside the Enterprise network and connects to the Lotus Domino or MS Exchange servers and acts as a connection to the NOC in Canada (the home of RIM and the location of the RIm NOC). The connection from the device to the NOC is encrypted and from the NOC to the BES is encrypted. Because of that encryption, there is no way for a government such as India, UAE, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia or other to intercept the traffic over either of the links (to or from the NOC)

Blackberry Topology

Last time I spoke to someone at RIM about this topology, they told me that RIM did not support putting the BES in the DMZ (where I would have put it) – since then, this situation may have changed.

Blackberry messenger traffic doesn’t get to the BES, but instead it goes from the device up to the NOC and then back to the second Blackberry which means that non-enterprise subscribers also have access to the messenger service and this appears to be the crux of what the various governments are concerned about. Anybody, including a terrorist could buy a Blackberry phone and have access to the encrypted Blackberry messenger service without needing to connect up their device to a BES which explains why they don’t seem to be chasing after the other VPN vendors (including IBM with Lotus Mobile Connect) to get access to the encrypted traffic between the device and the enterprise VPN server. Importantly, other VPN vendors typically don’t have a NOC in the mix (apart from the USA based Good who have a very similar model to RIM). I guess the governments don’t see the threat from the enterprise customers, but rather the individuals who buy Blackberry devices.

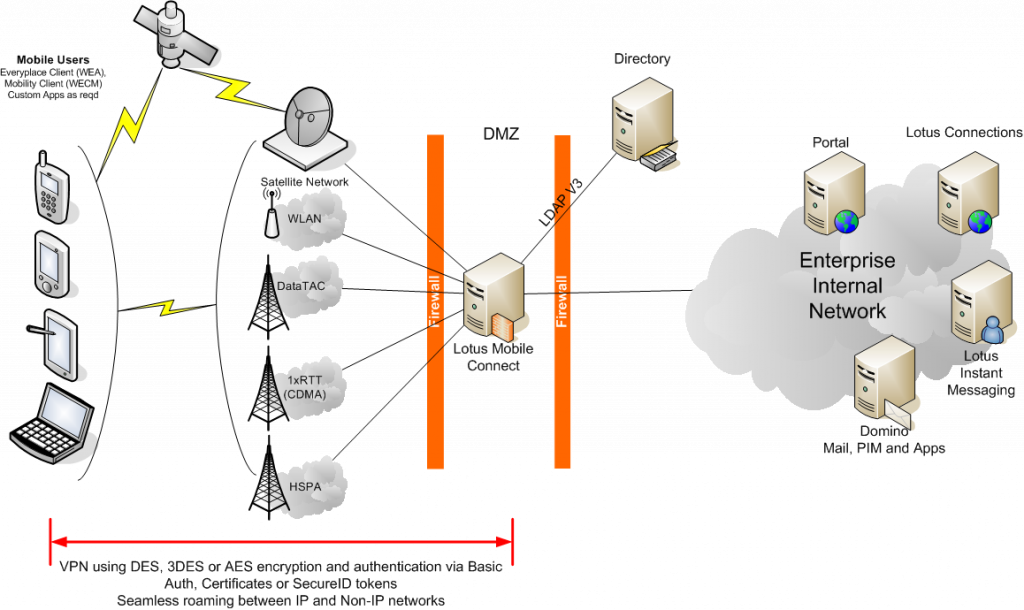

To illustrate how a VPN like Lotus Mobile Connect differs from the Blackberry topology above, have a look at the diagram below:

Lotus Mobile Connect topology

If we extend that thought a little more, a terrorist cell could set them selves up as a pseudo enterprise by deploying a traditional VPN solution in conjunction with an enterprise type instant messaging server and therefore avoid the ban on Blackberries. the VPN server and IM server could even be located in another country which would avoid the possibility of the government easily getting a court order to intercept traffic within the enterprise environment (on the other end of the VPN). It will be interesting to see if those governments try to extend the reach of their prying to this type of IM strategy…